Preface

The guidelines presented in this document are the result of a three-year (2011-2014) research project on audio description (AD) for the blind and visually impaired, financed by the European Union under the Lifelong Learning Programme (LLP). The basic motivation for the launching of the project was the need to define and create a series of reliable and consistent, research-based guidelines for making arts and media products accessible to the blind and visually impaired through the provision of AD.

These guidelines are intended for AD professionals and students to help them create quality services, but they also consider those people that have come into contact with AD in their personal or professional lives and who wish to better understand the challenges of the practice. The guidelines can be read in their entirety, but their structure also allows you to pinpoint a specific issue and browse the relevant item chapter. The chapters have been grouped in three sections: section 1 is an introduction to AD and introduces some related concepts. Section 2, AD scriptwriting, consists of the guidelines for writing audio descriptions for recorded AD, cinema and television more specifically. Section 3, Information on the AD process and its variants, provides a good insight into the various steps involved in the production of a finalised audio-described product. The chapters in section 3 are informative and have been designed to give you a maximum of insight and knowledge about the whole AD production process in a nutshell. To conclude, the guidelines also have a number of appendices: an example of an AD script and an Audio Introduction, a glossary with key terms and their definitions and finally a section with suggestions for further reading.

These guidelines have been edited by Aline Remael, Gert Vercauteren and Nina Reviers (University of Antwerp) and include contributions from the following authors: Iwona Mazur, Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Gert Vercauteren, Aline Remael, University of Antwerp, Anna Maszerowska, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Elisa Perego, Università di Trieste, Agnieszka Chmiel, Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu, Anna Matamala, Pilar Orero, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Chris Taylor, Università di Trieste, Bernd Benecke and Haide Völz, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Nina Reviers, University of Antwerp, Josélia Neves, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria.

We wish to take the opportunity here to thank all people involved in the ADLAB project, in particular: Manuela Francisco (Instituto Politécnico de Leiria) for her work on the e-book version of these guidelines, the members of the advisory board for their constructive suggestions, Alex Varley (Media Access Australia) and Jan-Louis Kruger (Macquarie University, Australia) and all the user associations, organisations, museums, providers, companies from all the partner countries that were so kind to contribute to the project, and everyone else who contributed in some way.

Additionally we would like to thank Pathé UK for letting us use the AD script of Slumdog Millionaire, thank Katrien Lievois, as we are indebted to her research on intertextuality in AD ('Audio-describing cinematographic allusions', paper presented at the International Media for All Conference, Dubrovnik, September 2013) and mention that contributions by Iwona Mazur and Agnieszka Chmiel have been partially supported by a research grant of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher education for the years 2012-2014, awarded for the purposes of implementing a co-financed international project (agreement number 2494/ERASMUS/2012/2).

Table of Contents

Introduction

Aline Remael, Nina Reviers, Gert Vercauteren, University of AntwerpThis introduction provides the necessary conceptual framework regarding audio description that you will need to make optimal use of these guidelines. It first gives a short definition of AD and its production process. Then it explains how stories are told in audiovisual materials, and introduces the main topics that are explained in greater detail in section 2, AD scriptwriting. Next a description of the target audience is provided, followed by a discussion of two thorny issues in AD: equivalence and objectivity. Finally, there is a section on how to use these guidelines.

What is Audio Description: A definition

AD is a service for the blind and visually impaired that renders Visual Arts and Media accessible to this target group. In brief, it offers a verbal description of the relevant (visual) components of a work of art or media product, so that blind and visually impaired patrons can fully grasp its form and content. AD is offered with different types of arts and media content, and, accordingly, has to fulfil different requirements. Descriptions of "static" visual art, such as paintings and sculptures, are used to make a museum or exhibition accessible to the blind and visually impaired. These descriptions can be offered live, as part of a guided tour for instance, or they can be made available in recorded form, as part of an audio guide. AD of "dynamic" arts and media services has slightly different requirements. The descriptions of essential visual elements of films, TV series, opera, theatre, musical and dance performances or sports events, have to be inserted into the "natural pauses" in the original soundtrack of the production. It is only in combination with the original sounds, music and dialogues that the AD constitutes a coherent and meaningful whole, or "text". AD for dynamic products can be recorded and added to the original soundtrack (as is usually the case for film and TV), or it can be performed live (as is the case for live stage performances).

Depending on the nature of a production additional elements may be required to render it fully accessible. In the case of subtitled films, the subtitles need to be voiced and turned into what are called Audio Subtitles (AST). Some films or theatre productions require an introduction (called Audio Introductions, AI) for various reasons. In the case of museum exhibitions, descriptions may be combined with touch tours or other tactile information. In all cases, websites can be used to provide additional information about a production or exhibition, provided they are accessible too.

Overview of the process from start to end

The creation and distribution of ADs is a complex process that requires the collaboration of multiple professionals from different fields: audio describers, voice talents or voice actors, sound technicians and users. Even if each AD provider has its own best practice, the production process for film and TV series usually includes the following steps:

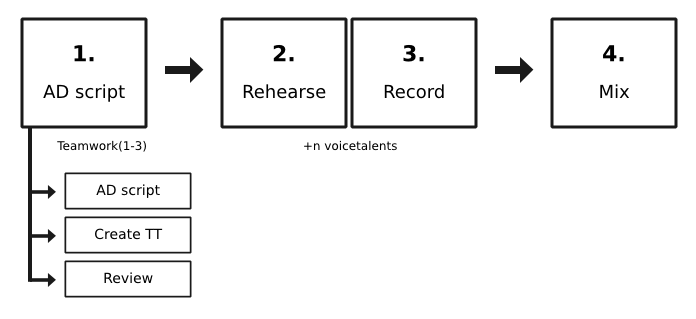

Figure 1: The AD production process

- (1) Writing the AD script:

- Viewing and analysing the source material (henceforth called “Source text", ST). This can include a blind viewing.

- Writing the descriptions in what is called the AD script (or “target text", TT) and timing them so as not to cause overlap with the other channels on the soundtrack, especially the dialogues.

- Reviewing the AD script while viewing the film. This can be done together with a blind or visually impaired collaborator.

- (2) Rehearsing the descriptions with the voice talents and making final changes where appropriate. Sometimes the writer of the AD script and the voice talent(s) are one and the same person.

- (3) Recording the AD with voice talents or synthetic voices.

- (4) Mixing the AD with the original soundtrack in the appropriate format (different for DVD, cinema, festivals, etc.).

The main focus of these guidelines is on the AD scriptwriting phase (step 1). This process is more or less the same for all types of AD, from film to theatre and visual arts. But the production process for live AD obviously does not include steps 3 and 4. The recording process for audio guides with AD is also quite different from that for film.

What is a story and how is a story told

One of the basic theoretical principles underlying the approach taken in these guidelines is that many films, TV programmes, theatre plays, etc. want to offer their audiences an experience that is driven by a story or narrative. Given their inherently multimodal nature, the stories told in these and other audiovisual products will only be partly accessible to blind and partially sighted audiences and it will be the audio describer’s task to provide the information to which these audiences do not have access, so that they can reconstruct the story told in the ST in the fullest possible way. This task consists of two parts that are also reflected in the structure of the different chapters in these guidelines: first describers must analyse their ST to identify what story filmmakers want to tell and what principles and techniques they use to tell their story. Then describers must decide what narrative elements to include in the TT or AD script and how to formulate the description.

The better audio describers know how filmmakers tell stories and how audiences reconstruct them, the better they will be equipped to create their AD. Therefore the following paragraphs will briefly introduce the main principles of story creation as performed by the filmmaker and of story reconstruction as performed by the audience.

Story-creation by an author or filmmaker

It is clearly beyond the scope of this section to discuss all the narratological principles underlying story creation at length, but broadly speaking story-creation is a three-stage process in which authors or filmmakers combine elements from two main narrative building blocks. In the first stage the author decides 1) what characters to include in the story and what actions they perform or undergo, and 2) in what spatial and temporal settings these actions will take place. In the second stage, the author will decide how exactly the story will be told:

- the author decides on the order in which actions will be presented. He can either present them chronologically or decide to change their order for various reasons: he can use a flashback to explain a specific character trait, or just to delay the action going on and hence create suspense. He can decide to present two different lines of action separately or interweave them to show parallels and differences between them. He also has to decide on the frequency of the actions: he can decide to show actions more than once (maybe from the point-of-view of different characters) or not show them at all, for example to raise questions in the audience. Finally, he has to decide on their duration, i.e. whether the actions are presented at their normal speed or in fast-forward (e.g. to omit unimportant parts of the narration or to create a comical effect) or in slow-motion (e.g. to reflect a character’s mental reaction to an action, or to slow down the narration to create suspense);

- the author decides on the specificities of the characters: their physical characteristics, their mental properties and their behaviour;

- the author finally has to fill in the spatio-temporal frame and its details. In other words, he has to decide in what time and place the actions will be set.

In the first two stages, the story is in fact an abstract construct and it is only in the third stage that the author decides how he will present it concretely. In the case of films and other recorded audiovisual products, this implies using different film techniques to decide what is shown (e.g. a close-up to depict a character’s emotional reaction to an event, or a panoramic shot to present a majestic landscape), how it is shown (e.g. a specific camera angle to represent the superiority of one character over another, a scene presented in black and white to signal this is a dream sequence) and what the relations between different shots are (e.g. a flashback to explain the movement of a character from one setting to another, etc.). One very important aspect with regard to these relations is that the author or filmmaker has to maintain continuity, i.e. that he must ensure that the techniques he uses to combine the various shots and scenes create a coherent and consistent whole. Not only do these techniques serve a narrative function, they are also used to determine the style of the ST and they ensure its cohesion.

In other words: story-creation is a highly complex process involving various stages and offering quasi endless possibilities when it comes to selecting and combining different elements. Only after a careful analysis of both content and style of the ST, can the describer create a description that mirrors this ST.

Story-reconstruction by the audience

Stories are never created in a vacuum. They are made to be read, listened to or watched by an audience that follows a path that is opposite to the one followed by the author, described in the previous section. In other words: audiences are presented with the concrete narrative, and they have to interpret and process it to arrive at the original, abstract (chronological) construct that the author started from. In part this is an individual process, dependent on the individual audience member’s knowledge and background. To a considerable extent, however, this story-reconstruction by the audience is a more or less universal process that we have all mastered. Audiences recreate stories according to general principles and better insight into these principles can help describers decide what to include in their descriptions and how to formulate them in order to make the story-recreation process easier for the blind and visually impaired.

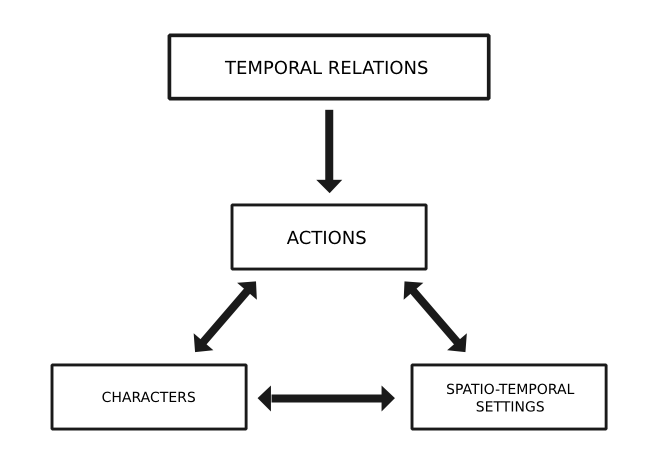

Basically, audiences reconstruct stories by creating mental models of them, i.e. mental constructs of who did what with and/or to whom, where, when and why. Again this introduction does not allow us to fully elaborate on the construction of mental models by audiences, but they can be presented schematically as follows:

Figure 2: mental models in story-reconstruction

Central in this representation are the actions that drive the story forward. Those occupy an essential position in the model, to which all other aspects are related. In other words, when audiences process and interpret a story, they will look at the actions that are being performed and combine them with other information from the story: the characters that cause and undergo them and the spatio-temporal settings in which they take place. In addition, they will process the temporal relations between the different actions shown, in order to reconstruct their chronological order. As the story progresses, audiences continuously update their mental model of the story, adding new information to it, confirming what was already there or what they inferred, and changing existing information or assumptions based on information they have received later.

Just like story-creation, this story-reconstruction is a highly complex process that can, in very generalising terms, be seen as comprising two levels. On a first level, audiences create frames that serve as a context for every event in the story. In these frames information on the characters that are present and the spatial and temporal circumstances in which the event takes place, take the form of general labels, i.e. “John”, “London”, “1997””. On the second level, additional, more detailed information is added to these labels: John is a dark-haired man in his forties, he lives in a flat in a specific neighbourhood. It is a sunny day in the summer of 1997. An example of a “frame” could be a character’s office, and an example of a representation, a detailed description of a particular office chair. Such a seemingly secondary element in the mise-en-scène can be important if it has a symbolic function.

When a new story event is presented, the audience will check whether it can be attributed to an already existing frame, whether an existing frame has to be updated (for example because the spatio-temporal setting has remained the same but characters leave the setting or new characters enter it) or whether a new frame has to be created (a new location, for instance). These frames form the basis for the comprehension of the story: when audiences cannot link an event (e.g. a murder) to a frame (e.g. a future inheritance) or cannot create a new frame for a certain event (e.g. an inexplicable change in relations between characters), they will no longer be able to follow the story (temporarily or permanently).

Translated to the context of AD, describers first and foremost have to make sure that their AD (in combination with the original ST) contains all the necessary cues to allow the blind and partially sighted audience to create a context for every event taking place in the story. In a second stage they select the more detailed information or "entity representations" that fit that particular context.

Audio description: From visual to verbal narration

The mixed target audience

The primary target audience of AD consists of blind and partially sighted viewers. However, this audience is very diverse. Some people were born blind (a minority), some became blind early on or later in life (e.g. as a result of an illness). Others have different degrees and different types of visual impairment. In brief, the target group is composed of subgroups that are all composed of individuals with different visual experiences and a different knowledge of the world. For economic and practical reasons, AD today aims to cater for all of these, which means that part of the challenge is to find a golden mean that will make the ST accessible to all.

In addition, AD is being used by an increasingly large group of sighted viewers for an equally varied number of reasons. Immigrants may use AD to learn the language of their host country, children may use AD as they are acquiring languages, people with ADHD may use the information provided by AD to help them focus on the programme. All this means that some users will still rely on the visual information to some extent, whereas others might use the AD as a talking book. This has important implications for synchrony between AD, sounds/dialogues and images.

Story-reconstruction, equivalence and objectivity

Audio describers are also viewers. This means that the filmic story as told by audio describers, will always be their own interpretation of the film. Different audio describers will produce (somewhat) different audio descriptions. In this sense, AD is similar to other forms of translation.

In Translation Studies (TS), equivalence is a term that is still used to refer to the relation between ST and TT but that is also regarded as problematic because such "equivalence" is very difficult to define and is never absolute. Any translation will have deletions, additions, reformulations etc. when compared with its ST. In the case of AD the concept is even more problematic: when is the verbal rendering of an audio-visual production "equivalent" to its aural/visual ST? No watertight definition is possible. On the other hand, AD does strive to give its target audience an experience that is comparable to that of the sighted target audience, which is itself composed of individuals who will all see the film differently.

However, watching films and TV series is also a social given: experiencing a film gives the blind and visually impaired an inroad into the social world of the sighted. Consequently, the AD is expected to respect the ST genre and the specific story it tells, allowing the aural filmic channels to contribute. In addition, watching a film is often a leasurely activity. This means that the AD does not merely focus on giving the information that is deemed to be missing, it also aims to create a pleasant experience for its users without overburdening their information-processing capacities.

Although "objectivity" is an AD aim that recurs in many of the earlier AD guidelines, no one ever sees the same film, as you will know from discussions with your friends. This is no different for the blind and visually impaired audience since it is just as heterogeneous as the sighted one. AD too is always subjective to some extent since it is based on the interpretation of the audio describer. Moreover, rendering images into words often entails making a visual piece of information more or less explicit, depending on the needs of the story, which always results in minor shifts in meaning. This is inevitable. It is also inevitable that the AD will "guide" the VIPs to some extent. Finding a balance between a personal interpretation and personal phrasing (subjectivity) and more text-based interpretation and phrasing (objectivity) that leaves room for further interpretation by the blind and visually impaired users is part of mastering the AD decision-making process and writing skills discussed in the various chapters of the present guidelines.

How to use these guidelines

The previous sections have illustrated the importance of a detailed analysis of the text and the context in which it is produced in order to create a professional AD that is clear and engaging. This analysis consists of a close examination of the source material, including background research about the text and its production. This then feeds into the decisions that you as a describer need to make about what to include in the TT and how, keeping the specific but heterogeneous target audience in mind. All the decisions you make regarding the AD will always be co-determined by the particular context in which a given narrative event (e.g. the introduction of a character) occurs and often there will be more than one option regarding how to describe it. The purpose of section 2, AD scriptwriting, is to help you make your own decisions and identify appropriate strategies.

Each chapter in this section is dedicated to one particularly thorny issue regarding AD scriptwriting (Characters and action, Spatio-temporal settings, Genre, Film language, Sound effects and music, Text on screen, Intertextual references, Wording and style, Cohesion) and follows the same basic structure. First it defines its topic. Next a section called "Source Text analysis" helps you to ask the right questions about this topic. These questions will allow you to analyse what the productions communicate to their users and how they do it. In particular, they will help you to better understand how the film medium guides the audience’s attention to the core elements of the narrative. Such insights will help you distinguish those core elements from secondary elements of minor relevance; an essential skill since time for description is limited in AD. Finally, the section "Target Text creation" will offer possible strategies for deciding how to translate these findings into an AD script.

Then, you will be able to develop your own decision-making process that generally includes the following steps:

- (1) Decide what narrative elements must ideally be included in the AD;

- (2) Locate the "silent gaps" in the ST, determine how long they are and how much AD can be added;

- (3) Decide what elements are also conveyed through other channels besides the visual, e.g. sound or dialogue;

- (4) Based on steps 1, 2 and 3, decide whether a given narrative element will be omitted (no time or redundancy with other channels) or whether it will be described. If in doubt, make a note that testing with a blind or visually impaired collaborator may be required;

- (5) Decide on an appropriate strategy for those elements that need description in terms of when to include the AD and how to formulate it.

There are a range of possible strategies for describing a narrative event with different gradations in the explicitness of description, that are explained and illustrated in each of the following chapters. Generally speaking, though, they imply a choice between "objectively" describing what you see on screen (a strategy located at one end of the scale), naming what can be seen more accurately (located somewhere in the middle of the scale) or explaining what the visual element means (located at the other end of the scale). An example:

“A flashback” versus “Back in 1930”

“Her eyes open wide” versus “She is amazed”

Or a combination of these:

“Her eyes open wide in amazement.”

The purpose of section 3 “Information on the AD process and its variants” is to better understand your role as an audio describer in the entire AD process. It will help you understand the decisions made by specialists regarding the other stages of the AD process, for instance, regarding how to edit or what voices to choose for the recording of the script. As it is good and even desirable to be aware of the process as a whole, this section includes chapters on technical issues such as preparing the script for recording or the supplying of audio subtitles. This will help you identify your place as the AD scriptwriter in the bigger picture and will get you acquainted with technical issues, the challenges of AD for multilingual productions and variants on recorded AD. In addition, section 3 contains chapters of an informative nature on the most important AD variants (Audio Introductions, Combining AD with audio subtitles, Audio describing theatre performances and Descriptive guides for museums, cultural venues and heritage sites). The appendices in section 4 provide you with a detailed glossary and reading list for further study.

AD scriptwriting

Narratological building blocks

Characters and action

Iwona Mazur, Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w PoznaniuWhat are characters?

Characters and their actions and reactions are an essential part of a film narrative, moving the story forward. Characters have a physical body, but they also have traits, such as skills, attitudes, habits or tastes. If a character has only a few traits, then they are said to be one-dimensional, if they have many traits (sometimes contradictory ones), they are three-dimensional. In film, traits of characters are usually revealed quickly and in a straightforward manner.

Source Text analysis

We get to know characters through their physical appearance, actions, and reactions (manifested, for example, by means of gestures and facial expressions), as well as through what they say and how they say it. For instance, in The Devil Wears Prada (Frankel, 2006) the way Andrea dresses (and the metamorphosis she undergoes) is an important part of the narrative. In Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009) Col. Landa’s meticulousness is depicted through his actions: the way he neatly arranges writing materials on the table when interrogating LaPadite, the way he eats strüdel at a Paris café when he talks to Shosanna. In All About Steve (Traill, 2009), on the other hand, Mary’s emotional reactions reflected in her extensive grimacing and fidgeting are an important part of her characterisation. And lastly, in Annie Hall (Allen, 1977) the neurotic nature of Alvy Singer is mainly manifested through what he says and how he says it. But characters can also be revealed to us by the way others react to them as well as by their environment (see chapter 2.1.2 on spatio-temporal settings) or by means of film techniques. For example, in Away from Her (Polley, 2006), the main character’s developing Alzheimer’s is reflected by the "patchy" editing (for more information on film techniques see chapter 2.2.1).

When analysing your ST you can use the following checklist to identify the nature and role of the characters.

- In a narrative there is usually at least one focal character (protagonist, antagonist). Focal characters push the story forward to the greatest extent. In addition, there may be supporting characters, whose role in a narrative is secondary, though their significance for the film, or a given scene, can be substantial. There are usually some background characters (played by the so-called extras). War films and epic films especially tend to employ a large number of background actors;

- Characters can be new or known. If a character is new, they appear in the film for the first time, if they are known, they appear again, looking either the same (or similar) or different. For example, in Tootsie (Pollack, 1982) Michael Dorsey, the main character played by Dustin Hoffman, starts to dress as a woman and transforms into "Dorothy Michaels";

- Characters may be used for the purposes of temporal orchestration (see chapter 2.1.2). For example, their changed looks can signify the lapse of time (e.g. Benjamin Button getting younger in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Fincher, 2008) or be used to signal a flashback or a flashforward. For example, in Slumdog Millionaire (Boyle & Tandan, 2008) Jamal Malik is 18 years old during the game show, but is presented as a 5-year old, 10-year old, etc. during the flashbacks, which do not correspond chronologically to Jamal's life, so the story switches between different periods of Jamal’s life (childhood, adolescence);

- Characters can be related or linked to each other. For instance, in The Wedding Planner (Shankman, 2001) the titular wedding planner Mary meets and falls for a man called Steve, who later turns out to be her client’s fiancé “Eddie”;

- Characters can be authentic or fictional. While fictional characters have been made up by the screenplay writer, authentic ones refer to actual persons. They can be played by actors (e.g. Virginia Wolf played by Nicole Kidman in The Hours (Daldry, 2002), or Julia Child by Meryl Streep in Julie and Julia, (Ephron, 2009)) or they can appear as themselves (the so-called cameo appearance). For example, in The Devil Wears Prada (Frankel, 2006) there is a cameo appearance of the fashion designer Valentino Garavani. Authentic characters can be either familiar or unfamiliar to the audience. With familiar authentic characters the assumption is that they are known to the majority of the target audience, while unfamiliar authentic characters may be unknown to them. This can be highly culture- or country-specific. For example, we can assume that the American chef and television personality Julia Child will be familiar to most of the American audience, but not necessarily so outside of the U.S. (also see chapter 2.2.4 on intertextual references);

- Characters can be real or unrealistic. The latter are especially popular in science-fiction, fantasy and children’s films, for example E.T. in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Spielberg, 1982), hobbits and gollums in The Lord of the Rings (Jackson, 2001-2003) or The Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz (Langley, 1939);

- Characters can have a symbolic function: they may represent a certain group of people, social class, profession, a stereotype or an idea. For example, in Rock of Ages (Shankman, 2012) Stacee Jaxx is a prototypical rock star, both in terms of looks and behaviour.

Target Text creation

Having analysed the types of characters in a film and the functions they perform, you can now proceed to create your description.

- Determine focal characters as well as any relevant supporting characters. These will most probably be the focus of your description. If there are any symbolic characters, decide what feature(s) make(s) them represent a given group or idea;

- Determine through what means characters and their traits manifest themselves most (e.g. physical appearance, actions, reactions, dialogues). This should give you an indication as to what to prioritise in your description. However, if there is sufficient time between dialogues, insert a description of a character’s looks even if it is not their most determining factor. This will help the blind visualise the story better;

- Determine whether there are any authentic characters in the film. If so, decide whether they may be familiar or unfamiliar to the target audience (see examples below). See if there are any cameo appearances relevant to the story;

- Identify any unrealistic characters and determine their most prominent features (see examples below). Decide whether to use any similes or comparisons to describe them, e.g. rabbit-like ears.

- Determine any relations or links between and among characters. Decide whether to name the links explicitly or let the audience infer them on their own, based on the dialogues or plot.

- Determine whether a character is new or known;

- If the character is new, decide whether to name them right away or wait until they are actually named in the film. When deciding, consider the moment they are named in the film or whether the character’s identity needs to be kept secret. If you decide not to name the character right away, use a short consistent description to identify them (see below). If the character is known, decide whether their looks have changed in a way that is relevant to the story or its temporal orchestration, signifying the lapse of time. If the character is hard to recognise at first, decide whether to say explicitly who they are or describe their changed looks and let the viewers infer their identity on their own, based on the context or dialogues;

- If the character is new, decide how to describe their looks. Determine the features that are the most unique about the character: a scar or a white beard. You can then use those features to consistently identify characters that are not named right away (see above), for example "a man with a white beard";

- You may also decide to describe a character gradually, adding a feature or two when the character reappears on the screen. It may be necessary due to time constraints or you may not want to overload the audience with a too lengthy and detailed description at one go, which could make their concentration lapse;

- Determine what actions and reactions of a character move the story forward to the greatest extent. Decide what words will most succinctly and vividly convey the character’s actions (see chapter 2.3.1 on wording and style). Identify gestures and facial expressions that best reflect their reactions and decide which of them to describe and which to leave out (see examples below);

- Determine what a character’s environment, as well as reactions of others towards them or the use of specific film techniques tell us about the character. For example, a character’s pedantic nature can be emphasised by describing how all items in their apartment are meticulously arranged. Decide which elements to describe and how (see chapter 2.1.2 on spatio-temporal settings). As for the reactions, instead of saying that a woman is beautiful, you could describe how men respond to her with awe and admiration. And finally, with film techniques (see the Away from Her (Polley, 2006) example above), decide whether and how to render them in your description (for more information see chapter 2.2.1 on film language).

Examples

An example of authentic characters from The Hours (Daldry, 2002):

- “Virginia Woolf” (name)

- “The English writer Virginia Woolf”(gloss + name)

- “A middle-aged woman with a slightly hooked nose and hair pulled back in a bun” (describe)

- “A middle-aged woman with a slightly hooked nose and hair pulled back in a bun, Virginia Wolf “(describe and name)

An example of unrealistic characters from The Lord of the Rings (Jackson, 2001-2003):

- “A hobbit” (name)

- “A short human-like creature with slightly pointed ears and large fur-covered feet” (describe)

- “A hobbit: a short human-like creature with slightly pointed ears and large fur-covered feet” (name and describe)

An example of gestures from Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009)

- “He makes the characteristic Italian hand gesture” (gloss)

- “He makes the ‘What do you want’ gesture” Or: “He makes the ‘annoyance’ gesture” (name the gesture)

- “His fingertips pressed together, turned towards his face” (describe)

- “He makes the Italian ‘What do you want’ gesture: his fingertips pressed together, turned towards his face” (name and describe)

An example of facial expressions from Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009)

- “Shosanna’s eyes are wide open. She’s gasping for breath” (describe)

- “Shosanna is petrified” (name the emotion)

- “Shosanna’s eyes are wide open in terror” (describe and name the emotion)

Spatio-temporal settings and their continuity

Aline Remael, Gert Vercauteren, University of AntwerpWhat are spatio-temporal settings?

All stories take place in particular spatio-temporal settings (in the remainder of this section referred to as "settings"), which comprise both a temporal and a spatial dimension. These settings are intrinsically linked to the characters and their actions (see chapter 2.1.1) as they take place in the story (i.e. there can be no actions without a setting). Settings are therefore one of the basic narrative building blocks (see chapter 1 introduction) and as such require specific attention in the description. In addition, the importance and function of time and setting may change in the course of the story These changes are signalled in the text by cues, i.e. various film techniques (see chapter 2.2.1), which describers must pick up when analysing the ST.

The different settings of a filmic story are also linked to each other through editing (see chapter 2.2.1) and the way they are linked can reflect different temporal relations between them. They can follow each other either chronologically or in flashback or flashforward. The time period that has elapsed between scenes will vary. We will refer to this time factor as that of temporal orchestration.

Source Text analysis

When analysing your ST for spatio-temporal settings and the connections between them, you can use the following checklist of the major spatio-temporal features to identify their precise nature.

- Settings can be global (e.g. a mountain range, as in the opening scene of Brokeback Mountain (Lee, 2005) or local (e.g. an interrogation room, as in in the opening scene of Slumdog Millionaire (Boyle & Tandan, 2008). During the film, and even within scenes, these settings can move from global to local, or the other way around, as in the opening scene of The Forgotten (Ruben, 2004), starting with a global bird’s eye view of a city, and moving to a more local or specific location, namely a playground in a park;

- Settings can be background to the action or serve a narrative/symbolic function. A police office, for instance, may simply be the backdrop for part of the action of a crimi. A castle, by contrast, may symbolise the power of its inhabitant, whereas a dilapidated castle may indicate the downfall of that person. An island, or an asylum on an island, may suggest confinement, as in Shutter Island (Scorsese, 2010);

- Settings can be real or imagined. A setting that is real, is experienced as such by the characters in the fictional world of the story, a setting that is imagined may exist only in the mind, memory or dreams of one of the characters (e.g. in the film versions of Alice in Wonderland (Burton, 2010)).

- Settings can be new or known. A new setting is one that is introduced for the first time. A known spatio-temporal setting is one to which a character or the action returns in the course of the story. This known setting can be precisely the same as when it was shown first, or it may have changed (e.g. in Ransom (Howard, 1996)) the penthouse where the protagonist lives, is a warm, welcoming place in the opening scene, but becomes a much colder environment after his son is kidnapped and the struggle to get him back, intensifies);

- Settings can be presented explicitly or implicitly. In the opening scene of Slumdog Millionaire (Boyle & Tandan, 2008) the text on screen "Mumbai, 2006" tells us explicitly when and where the story is taking place, while in Girl with a Pearl Earring (Webber, 2003), the 17th century setting is presented implicitly by means of the buildings and the characters’ clothing.

- Settings can be well-known or unfamiliar and how they are identified, in this case, will depend on the background and knowledge of the viewer, including the describer. St Paul’s Cathedral in London will be recognised as St Paul’s by some, as a large church or cathedral by others. However, the location may be mentioned explicitly by the film (see previous item);

- Settings are related to each other and/or to characters and their actions. In The Hours (Daldry, 2002), for example, the three main characters are each linked to one specific setting: Virginia Woolf to London, 1923; Laura to Los Angeles, 1951 and Clarissa to New York, 2001. As such, a setting will sometimes be identified by a character, because it is known that this character is connected with that setting.

- All the different functions identified above can be signalled by film editing, film techniques, dialogue and/or sound effects/music, that is, by the different communication channels of the film (see chapters 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 respectively).

Target Text creation

Having analysed a given setting and its relations to the preceding one(s) and to the other narrative elements in it (such as the characters, see example The Hours (Daldry, 2002)), you proceed to create your description. First decide what must be included. For more information on how to describe, see chapter 2.3.1 on wording and style as well as chapter 2.3.2 on cohesion.

- Determine through what channel the spatio-temporal information is provided (i.e. is it presented visually and does it have to be described, or can it be derived from the dialogue or a sound effect). Decide whether to describe it or not. However, if there is sufficient time between dialogues, include the information in your description. Information that is repeated through different channels may help your target audience identify it;

- Determine whether a setting is new or already known;

- If a setting is new, determine whether it is global or local, real or imagined, serves as a background or has a narrative-symbolic function. Decide what and how much to describe: backgrounds need minimal description that allows the audience to identify a place. Settings that have more symbolic functions need more detailed descriptions. Global settings will be described in more general terms, descriptions of local settings will include more detail. The difference between real and imagined settings can be indicated, for example, by describing how a character stares at a photograph, while his mind wanders (in Nights in Rodanthe (Wolfe, 2008), the protagonist looks at a photo and then his mind wanders to a scene from his past). Identify which aspects of the setting are most important for the story and should get priority in the description. Describe features that are typical and that you will be able to use later for reference when a setting returns (think of the user’s mental model of the story discussed in chapter 1);

- If a setting is known, determine if it is identical (repetition), if something has been added (accumulation) or if the setting has undergone a complete transformation. Decide how to signal this: identical settings can be described briefly with one or two of the features used to describe it before (e.g. Back at the office); if something has been added this new information needs to be described (e.g. The office. The painting has disappeared); if the setting has undergone a complete transformation, describe what has changed (e.g. from a castle to a dilapidated castle);

- Determine the relations between settings and the characters in them and/or their actions. If a setting is new, make sure that you identify these relations (e.g. A single-storey home in a Los Angeles suburb, 1951, Laura is reading Mrs. Dalloway, The Hours (Daldry, 2002). If the setting is repeated you can simply refer to one of its features (e.g. Back in Los Angeles; Back in 1951; Back with Laura) and the rest of the setting will also be "activated" in the user’s mind;

- Determine whether a spatio-temporal setting is presented explicitly (e.g. through text-on-screen, see chapter 2.2.3, indicating a specific place or through a secondary element, like a clock indicating time) or implicitly, and whether it is familiar or unfamiliar (e.g. Eiffel Tower vs. Charles river). In the case of an explicit reference, your description can just mention it (e.g. London, 1923). In the case of an implicit reference, decide if you want to keep the reference implicit, describe it and name it, or only name it, depending on the (recurring) function of the setting in the story and the time available for the AD.

Examples

- “A large white spiral-shaped building” (implicit reference/description)

- “The white spiral-shaped building of the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan” (describe and name)

- “The Guggenheim museum in Manhattan” (name)

Genre

Anna Maszerowska, Universitat Autònoma de BarcelonaWhat is genre?

Genre is a way of classifying films, of identifying them according to specific repetitive formal, aesthetic or narrative features. There are many different genres in cinema: comedy, melodrama, action, thriller, western, etc. The label of a particular genre can help the audience formulate their general expectations of a film: in a musical, (part of) the dialogues will be expressed (and/or replaced) by songs, in a horror movie, there will be threatening music, startling scary moments, and ambiguous focalisation, whereas drama will most likely feature a confused and torn character. Nowadays however, it is more and more difficult to ascribe a given film to a particular genre. Most films mix elements belonging to different genres, thereby creating new definitions and hybrid categories (e.g. romantic comedies, science fiction horrors).

One genre that still is clearly recognisable and usually differs considerably from other, more narrative genres or fiction films, is the documentary genre, usually considered to be non fiction. Even documentaries have subgenres, but, generally speaking, they tend to be more informative, include more or less objective accounts of facts, historic events, social issues or natural phenomena. They often have an entertaining dimension too but this is usually secondary. From a formal point of view, documentaries more often rely on off screen narration and interviews.

Source Text analysis

When analysing your ST from the genre-related point of view, you can use the following checklist:

- Genre is visible on many narrative levels. As you watch the film, pay attention to elements of iconography. Symbolic objects or settings and iconic items can be used to strengthen the character of the image. For example, a science-fiction film is bound to feature a space ship or a time capsule (Back to the Future (Zemeckic, 1985)), in a war film military uniforms and equipment will abound (Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg, 1998)), and in a horror movie there will be a blood-stained axe or saw (Cold Creek Manor (Figgis, 2003)). Other props may be indicative of the epoch or historical period in which the action of a film is set. This applies above all to costume films e.g. Pride and Prejudice (Langton, 1995) where pieces of clothing or furniture situate the film in a more or less specific time period;

- The film’s visual style or film language may be an important indication (see chapter 2.2.1 on film language). Pay attention to lighting, editing, mise-en-scene, and mise-en-shot. They are important when creating coherent descriptions that match the visual feel of the image to the narrative genre. For example, a comedy will often be shot in high-key lighting to add to the light-hearted atmosphere (Hitch (Tennant, 2005)), an action film can feature rapid shot changes and short average shot lengths to heighten the pace of the events (e.g. Deja Vu (Scott, 2006)), a horror movie will make extensive use of off-screen space and indefinite and/or ambiguous focalisation to convey suspense and tension (e.g. The Ring (Verbinski, 2002)), and a documentary will feature many close-ups and medium shots to better focus on the specialists sitting in front of the camera during an interview (The Imposter (Layton, 2012)), or long shots to render the vastness of a landscape;

- Some "pure" genre films will also depict certain prototypical or even stereotypical character types, who represent specific personalities and patterns of behaviour. In a crime film there will be a villain and a good person (e.g. a police officer as in The Brave One (Jordan, 2007)), a romance will feature a couple in love (The Notebook (Cassavetes, 2004)), and an adventure movie can star, for example, a group of friends setting out on a journey together (The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (Jackson 2001).

Target Text creation

In terms of preparing the actual AD script, the ability to classify a given film as representative of a particular genre is of relative importance. Genre will be more important for determining global strategies rather than local ones and explicit references to genre in AD are rare, except in cases of intertextuality (see chapter 2.2.4). Nevertheless, establishing that your source film belongs to a specific genre can help you to set priorities. When creating your AD, you may want to consider the following checklist:

- Determine what elements of iconography appear on the screen and observe whether they are only presented visually or are also referred to in the dialogue, off-screen narration, voice-over, etc. Decide whether you will describe the element or not (see also chapter 1 Introduction), and what strategy you will use: a general description of the element that implicitly refers to the genre (e.g. a blood-stained axe, a futuristic spaceship), or a more explicit and explanatory one if there is time. If the element is already referred to verbally, you may wish to omit it from the AD except if the item is particularly relevant for the genre of the film and you want to render it more explicit;

- Determine what genre-specific props are used and if you know their names. Decide if you want to describe them and what strategy you will use. You can, again, simply name the object, give a generalising description or name and explain the item. What seems to be an unimportant prop can be important in a specific genre, even though at first sight it seems to be a secondary element. The last option allows you to provide additional information on objects that could otherwise remain ambiguous;

- Determine what elements of the visual style or film language of the film (see chapter 2.2.1) refer to its genre. For example, a lot of the action of a crime film will take place at night, on the streets, perhaps in a bad part of town (The Brave One (Jordan, 2007)). A specific mood can be rendered through the use of lively or bleak colours (Contagion (Soderbergh, 2011)). If these features are crucial for the story, use words that faithfully render the feel of such scenes (see also chapter 2.3.1 on wording and style);

- Determine the way characters are portrayed and see if there are any direct relations to the film’s genre. Often, villains are shot in dim lighting, surrounded by dingy settings, with their faces obscured by the shadows (The Lovely Bones (Jackson, 2009)). Decide whether you express those qualities directly, e.g. by describing the character’s movements, gestures, or facial expressions, or whether you render the relation to the genre indirectly, for example by describing the grim setting (See also chapter 2.1.1 on characters and chapter 2.1.2 on spatio-temporal settings);

- Determine whether there are specific aspects of focalisation and shot representation relating to the genre. Unclear focalisation in a crime film may leave the audience in doubt as to who is seeing what, thereby creating suspense. Decide if and how this will be described, for example, indicating that whoever is watching can only see part of the scene;

- For the AD of documentaries, additional decisions may have to be taken. First, you will have to determine if and where description is still needed, as much of the visual information is probably already contained in the off-screen narration or interviews. It may suffice to use text-to-speech AST, given the informative nature of the verbal part of the ST (see chapter 3.3 on AST and 3.1 on technical issues for information relating to choosing and recording voices).

Film techniques

Film language

Elisa Perego, Università di TriesteWhat is film language?

The accepted systems, methods, or conventions through which a film’s story comes to the audience, are known as film language. Film language is flexible and is based on the more or less conventional quality, form and combination of shots. It serves to communicate with the audience, to guide their expectations, to shape their emotions, etc. Film language also gives a film its distinctive shape and character, i.e. its style and its aesthetic value.

Film language is the sum of a combination of various film techniques that are all used simultaneously and that can be grouped into three broad categories: mise-en-scène, cinematography and editing. Mise-en-scène refers to what is being filmed in a shot and includes setting, costume and makeup, and staging. Cinematography deals with how shots are filmed and comprises their photographic qualities, framing and duration. Editing refers to the relations between different shots, which include a graphic, rhythmic, spatial and temporal dimension. In other words, film language determines the form in which the story is told.

Film techniques can serve four different functions: a denotative function (showing what is important for the narrative), an expressive function (rendering a character’s emotions or eliciting a mood or emotion in the audience), a symbolic function or a purely aesthetic function.

Source Text analysis

Film techniques usually coexist and a careful analysis is needed to identify and isolate them and their respective meanings. Not only do film techniques show the audience what is important in an image, they can also guide or confound the viewer's expectations depending on how clearly, consistently, coherently and conventionally they are used. They can be used to generate suspense or surprise and to elicit more longstanding moods in the audience. In other words, they determine both what is told and how it is told, and are therefore just as important as the actual narrative building blocks of the film. When analysing the film language of your ST you can use the following checklist to determine what film techniques are used and what their specific meaning is.

- Film techniques can determine what is presented to the audience in a specific shot, how it is presented and what the relations between successive shots are;

- When a film technique determines what is presented, i.e. when it belongs to the broader category of the mise-en-scène, there are three basic possibilities. It can deal with the setting of a specific shot, i.e. how the different elements in the shot are organised. An analysis of this composition may indicate what is more important (usually central elements in the shot) and what is, both literally and figuratively, peripheral. Second, it can deal with costume and makeup. Again, these can be used to guide the audience’s attention to the most significant elements in the image. Costume, in particular, can also be used to indicate the general time period in which a film is set. Finally, mise-en-scène deals with staging, i.e. the movement and the performance of the actors (see chapter 2.1.1 on characters and action for more information on this aspect);

- When a film technique determines how the information is presented, i.e. when it belongs to the broader category of cinematography, you will have to pay attention to three main issues, each encapsulating several meaning-making practices. First, there are the shot’s photographic qualities which comprise colour, speed of motion, lighting, camera angle and focus. In Women in Love (Russel, 1969) for instance, the bright colours of the opening scene give way to the pale and softer hues of the film's middle portion and to the film's last section's predominantly black-and-white scheme that represents the characters' cooled ardor. In Déjà Vu (Scott, 2006) slow motion is used to render the main character’s mental reaction to the dramatic aftermath of a terrorist attack. On a more general level, focus is another technique that is used to show the audience what is most important in the image. Second, there is the framing of the shot, i.e. the technique that determines what is presented within the film frame, in other words what you see and how you see it. Framing is intrinsically linked to the various types of shots, ranging from extreme long shots to extreme closeups. In The Shining (Kubrick, 1980), a helicopter shot opens the scene thus emphasizing the contrast between the majesty of the landscape and the insignificance of the protagonist's car. On the other hand, in Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009) Shosanna's eyes fill the entire screen in an extreme closeup, which isolates this character from the ongoing action and emphasises the emotional intensity of the moment. Finally, cinematography deals with a shot’s duration. A long take can be used to allow the audience to appreciate a certain landscape, or to reflect boredom. Short shot lengths, on the other hand, can be used to create suspense or to reflect a character’s restlessness;

- When a film technique determines the relations between different shots, i.e. when it belongs to the broader category of editing, you have to pay attention to four different types of relations. First, the relation between successive shots can be graphic. In Memoirs of a Geisha (Marshall, 2005), a shot showing cherry blossoms being carried away by the wind slowly gives way to a following shot in which the cherry blossoms are graphically matched to snowflakes, indicating a leap forward in time. Successive shots can also be related rhythmically, when different shot lengths in a scene are combined to form a specific pattern. In action scenes for example, successive shots will become shorter to reflect the increasing suspense and to arouse tension in the audience. Third, there are so-called spatial relations between successive shots: a filmmaker can start by showing a general space by means of a general establishing shot and zoom in on a detail within this space in the next shot. Finally, shots are also related temporally: two successive shots can either follow each other chronologically, or they can constitute a flashback or flashforward.

When you have analysed what film techniques are used in a certain shot/scene you can proceed to determine their function. First of all, a technique can have a denotative function, i.e. it can be used to guide the audience’s attention to the most important elements in the frame (e.g. a woman in a white dress surrounded by men in black tuxedos). Film techniques can also have an expressive function. Specific colours can be used to reflect the mood of the characters (cf. the Women in Love (Russell, 1969) example above) or they can be used to generate a certain emotion or mood in the audience (e.g. fast editing to create suspense). Film techniques can also have a symbolic function. In Away from her (Polley, 2006) discontinuous editing is used to symbolise the protagonist’s advancing Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, film techniques can serve an aesthetic function, for example when particular colour schemes are used because they are pleasing to the eye.

Target text creation

Having analysed the film language and the film techniques used in a given shot or scene, you proceed to create your description. However, keep in mind that most cuts from one shot to another are left undescribed in ADs, especially when scene changes do not have a particular added meaning. In a short excerpt from The Hours (2002) which includes five scene changes, none is made explicit in the AD, which simply juxtaposes the description of the different scenarios: "As the woman’s head sinks beneath the water, the man drops the letter to the floor and runs towards the back door. The woman’s body, face down, is carried by the swift current through swaying reeds along the murky river bed, her gold wedding band glinting on her finger, a shoe slipping off her foot".

First determine what category the techniques you encountered in a shot or scene belong to:

- if a technique belongs to the category of mise-en-scène, determine whether it deals with the setting of that shot or scene, with costume and makeup or with the staging;

- if a technique belongs to the category of cinematography, determine whether it deals with the shot’s or scene’s photographic qualities, with the framing or with the duration of the shot;

- if a technique belongs to the category of editing, determine whether it organises the graphic, rhythmic, temporal or spatial relations between two shots or scenes.

Next determine the function the techniques serve. It is important to realise that a technique can never be dissociated from the function it serves and that this function will determine to a large extent if and how you will describe the technique:

- if a technique serves a denotative function, i.e. when it wants to draw attention to narratively significant information, decide whether the information it highlights needs to be described, or whether this is already known from previous scenes or other channels. Costumes, for example, can indicate that a scene is set in a specific century, but this can also be signalled through a text on screen. In this last case, the describer can decide not to describe the costumes and give priority to other information, such as actions;

- if a technique serves an expressive function, determine whether it expresses an intra-diegetic emotion or mood of one or more of the characters, or whether it wants to generate an emotion or a mood in the audience. In the case of an intra-diegetic expressive function, decide whether the emotion it wants to render can be derived from other information, such as a line of dialogue. If so, you may decide not to repeat the emotion and prioritise other information. If not, the emotion can be expressed in the description. If the technique wants to create a certain mood in the audience, the decision-making process will be somewhat different: as the technique does not give any narrative information, you will not have to decide what you will describe (e.g. “the dark colours want you to feel sad”). Rather, you will have to determine whether the mood is also generated through other channels, such as the music, and decide if you want to repeat it in your description and how: creating a certain mood in the audience through an AD can for example be achieved by using a specific type of language or by voicing (see chapter 3.1 Technical issues) the description in a way that reflects the mood created by the filmmaker;

- if a technique serves a symbolic function, determine what it symbolises and whether the information symbolised can be derived from other channels or earlier descriptions. If it is already clear, decide whether to repeat it or give priority to other information. If it is not clear, decide if and how to include the symbolic information in the description. Again, this will imply deciding how to render this information: you can decide to explain the symbolic meaning, i.e. describe it in an explicit way, or render it in an implicit way and leave it to the audience to extract the symbolic meaning from your description;

- if a technique serves an aesthetic function, the decision you have to make is again if and how you will render it in your TT. You can decide to focus exclusively on narrative content and leave the aesthetic function aside, or you can render the narrative content by using a specific language (see chapter 2.3.1 on wording and style) or by voicing the description in a way that reflects the aesthetic function of the technique used.

Finally, decide how you will describe the technique. Basically you can decide to name the technique (“now in close-up”), to name it and describe its function (“a close-up reflects the fear in her eyes”) or only describe the function or meaning of the close-up (“fear is reflected in her eyes”). The decision of when and how to describe a technique will also depend on the film’s (director’s, genre’s, studio’s) style. If the technique is not significant, you can decide not to describe it. If on the other hand, a technique is very significant, occurs frequently, contributes greatly to the style, you might want to make sure that you convey that in your AD. If you need to mention the same technique more than once, use the same linguistic formulation throughout the AD text. Coherence and cohesion (see chapter 2.3 The language of AD) are important and can be maintained in AD also through a consistent use of cinematic language.

Examples

An example of cinematography from Déjà Vu (2006) rendering ATF agent Doug Carlin’s reaction when he sees the body bags on the quay after an explosion on a ferry kills dozens of people:

- "Now in slow motion. Doug walks past the body bags lined up on the quay." (name the technique)

- "Now in slow motion. Taking in the emotional scene, Doug walks past the body bags lined up on the quay." (name the technique + describe its meaning/function)

- "Taking in the emotional scene, Doug walks past the body bags lined up on the quay." (name the function/meaning of the technique)

Another example of cinematography from The lady vanishes (Hitchcock, 1938): the properties of the shot, which determine the style of the film, could be described in various ways.

- "Now, in black and white footage, a mountain top view looks down over a village nestled in foothills" (name the technique).

- "In a 30s movie, in black and white footage, a mountain top view looks down over a village nestled in foothills" (describe the function/meaning of the technique + name it).

- "In a 30s movie, a mountain top view looks down over a village nestled in foothills" (describe the function/meaning of the technique)

An example of Editing from Nights in Rodanthe (Wolfe, 2008): a man thinks about the day that drastically changed his life. He is lying on a bed and looks at a photograph that triggers different memories. The flashback could be described in various ways:

- "Lying on his bed, Paul studies an old photograph. A flashback" (dialogue) (name the technique)

- "Lying on his bed, Paul studies an old photograph and he thinks back to that last surgery. A flashback" (describe the function/meaning of the technique + name it)

- "Lying on his bed, Paul studies an old photograph as his mind starts wandering." (describe the meaning of the technique).

Sound effects and music

Agnieszka Chmiel, Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w PoznaniuWhat is film sound?

Sound in film comprises speech (in the form of film dialogues, voice-over narration and lyrics), sound effects and music. Sound effects and music may be used in film to create a mood, indicate a temporal or local setting (see chapter 2.1.2), enhance or diminish realism, create suspense, define a point of view (by manipulating the sound volume). Sound can guide the viewers’ attention and co-create the narration by highlighting specific visual elements that might otherwise seem secondary elements. The AD will become part of the soundtrack and rely on the information conveyed by its different components. It is important to ensure cohesion between these components (see also chapter 2.3.2 on cohesion).

Source Text analysis

In your analysis, it may be advisable to (also) listen to your film without watching the images to identify sounds that might otherwise escape you. When analysing your ST for sound to determine its usefulness for your AD, you can use the following checklist.

- Sounds can be diegetic (i.e. belong to the reality depicted in the film) or non-diegetic (i.e. be external to it). A diegetic sound is, for instance, a car engine whir in the opening scene of Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009) when a military column approaches a cottage. A non-diegetic sound is usually music or an off-screen voice (e.g. of a narrator, as in Vicky Cristina Barcelona (Allen, 2008);

- Diegetic sounds can be internal (e.g. the protagonist’s thoughts audible to the viewer) or external (audible to other protagonists, as well);

- Sounds can be on-screen, when their source is visible on the screen, or off-screen, when the source is not visible. Steps are an example of the former when a walking protagonist is visible in the scene or of the latter when instead we see another protagonist’s reaction to the as yet invisible approaching person;

- Sounds can be individual (e.g. the thud of an object falling) or form a soundscape (e.g. sounds of sirens, engines and walkie talkies in The Girl with a Dragon Tattoo (Fincher, 2011) when emergency services are in attendance at the scene of a car accident).

- Sounds can be simultaneous or not simultaneous with the visuals. A sound flashback is an example of the latter, when we see a protagonist in the present and hear a conversation from the past that the protagonist is remembering;

- Sounds can have an illustrative or symbolic function. Illustrative sounds enhance realism and are congruent with the depicted settings or objects. Symbolic sounds may, for instance, symbolise the protagonist’s dreams. In a Polish TV series Londyńczycy [The Londoners] (Zglinski, 2008), a 10-year old boy, Stas, is visiting his mother, who works in London. He skips language classes one day and goes to see Wembley Stadium. The place is empty but we can hear football match sounds (national anthem sung by football supporters, cheering crowds) that symbolise Stas’s dreams of becoming a successful player;

- Music in film can be instrumental or with vocals. The lyrics of the latter are usually meaningful for the narrative, especially in musicals.

Target Text creation

When analysing the sounds in your film, you can use the following checklist to determine whether and when they have to be mentioned in the AD, then how (much) to describe.

- Regarding dialogues or speeches with very short pauses, determine if the visuals are important enough to be audio described. If not, the dialogue is always a priority in AD. However, sometimes the AD will be given priority, as e.g. in The 39 Steps (Hitchcock, 1935). During a public speech by the main protagonist, a woman reports him to agents who are waiting for him to finish in order to arrest him. The description cannot fit in the pauses and has to cover the speech as the visual information is more important for the story than the words the protagonist is speaking;

- Determine if the sound effect is easy to identify (either aurally or through a reference in a dialogue) or not. If it is not, the best option may be to name the sound or its source in the AD;

- Determine if it is important to identify the source of the easily identifiable sound (e.g. who punches whom) or whether it is important to know just what produces the sound (e.g. a squeaking door or a squeaking bird), and decide if AD rendering the source explicit is required;

- Determine whether the sound is diegetic or non-diegetic. If it is non-diegetic (e.g. off-screen voices) determine whether it is clear who is speaking and whether it is important to know that, and in that case decide whether a reference in the AD is required. If the sound is diegetic, determine whether it is external or internal. If it is external, use the guidelines above, if it is internal, determine if it requires a special mention in the AD, and if in doubt, identify the sound;

- If the sound is individual and requires AD (because it is difficult to identify unequivocally: see above), determine when to describe it. Sometimes there will be no choice because a pause will be available only before or only after the sound. According to some, it is better to offer AD after the sound in order to maintain a dramatic effect. According to others, it is better to offer AD before the sound because it will help the audience to recognise the sound more quickly and reduce the effort required. Decide in each instance, on the basis of the context, what works best (see also chapter 2.3.2 on cohesion);

- Determine the function of the sound. If it is illustrative, decide if it must be mentioned in AD explicitly and how much description it requires (e.g. in the case of the sounds characteristic of a restaurant, the AD of the spatial setting of the scene might be sufficient, such as "in a restaurant". Alternatively, you may decide to add more details, "in a restaurant, people laughing and talking"). If the sound is symbolic and not congruent with the visuals, decide how much AD is needed to highlight the incongruence;

- Determine if the sound is non-simultaneous and decide if it requires an explicit mention in the AD. If you decide to mention a sound flashback in AD, you can do it either directly (e.g. "a flashback" or "in a flashback") or indirectly (for instance by describing it as the protagonist reminiscing);

- If dealing with music with vocals, determine how meaningful the lyrics are and whether describing the visuals is important for the narrative. If the lyrics are not meaningful and the visuals not important, decide how much description is needed. If the lyrics are not meaningful and the visuals are important, describe what is happening during the song. If the lyrics are meaningful and the visuals important, decide to what extent the AD may overlap with the lyrics. Use either synchronous description (i.e. describe the visuals as they appear on the screen) or asynchronous description (i.e. describe them earlier or later so as to leave the lyrics of the first verse and the first chorus audible).

Examples

- “Charles rolls the door closed.” (describe the source of a non-recognisable sound)

- “Andy chuckles at the similarity of the two blue belts.” (name the sound and source required in a group scene)

- “Shouts off-screen.” (idenitfy off-screen sounds)

- “Jamie’s thoughts.” (identify an internal diegetic sound)

- “Mary looks at a photo of her son.” (identify an internal diegetic sound: the protagonist’s thoughts about her son)

- “She looks through the window, deep in thought. A flashback.” (directly refer to a sound flashback)

- “She frowns as she remembers an earlier conversation with John.” (indirectly refer to a sound flashback)

Text on screen

Anna Matamala and Pilar Orero, Universitat Autònoma de BarcelonaWhat is text on screen?

Text on screen refers to any type of written text that appears on the screen. Text on screen includes opening credits and end credits, titles, intertitles, and other superimposed titles. Other non diegetic elements such as logos and diegetic elements which are part of the scene (a letter, a text message or a wall poster, for instance) may also contain written language. Subtitles can also be considered as text on screen: they can either appear as part of the original film (especially in multilingual productions) or they can be a translation of original dialogues for other audiences (see chapter 3.3 on AST).

Source Text analysis

When analysing your ST, you can use the following checklist to identify the function and relevance of each text on screen.

- Text on screen can belong to various categories and fulfil different functions. Determine what type of text on screen you are dealing with (opening or end credits, title, intertitles, other superimposed titles or inserts, logos with text, text on other diegetic supports, subtitles, other) and its function and relevance within the narrative. For instance, opening credits may be used not only to list the main film crew members but also to convey additional intertextual meanings (see chapter 2.2.4 on intertextual references) through a specific typeface. The opening credits of Sin City (Miller et al., 2005), for instance, copy the typical typeface of comic books. Superimposed titles may be used to identify the name of a character on screen;

- Text on screen can be part of the action (diegetic) or may have been added later, during the editing process (non-diegetic);

- Text on screen can bring in information which is unique or redundant. For instance, a superimposed title may be referring to a spatio-temporal setting (see chapter 2.1.2) that a dialogue or an off-screen narrator already makes explicit, hence providing the same information via an oral and a written channel;

- Inserts or superimposed titles can help identify many elements such as the spatio-temporal settings or a character (see chapter 2.1.1). For instance, in the film Inglourious Basterds (Tarantino, 2009), an intertitle reads "Once upon a time… in Nazi occupied France" and is followed by a caption that says "1941". In the same film, another caption helps the audience identify a character when she is shown as an adult for the first time ("Shosanna Dreyfus. Four years after the massacre of her family").

Target Text creation

Having analysed a given text on screen, you proceed to create your description and may consider the following elements.

- Determine what sort of visuals and meaningful sounds and/or lyrics appear simultaneously, if any, and determine if the information provided by the text on screen is already offered by other means (for instance, dialogue). Based on the previous elements, decide whether or not it is necessary to render the text on screen orally in your AD and, if so, decide what strategy you will use to render it, e.g. literal rendering, or a (condensed) paraphrase. Additionally, establish whether you will render the text on screen synchronically, before it actually appears on the screen or afterwards, taking into account the available silent gaps (see also chapter 2.3.2 on cohesion);

- Determine whether or not the typographical features used have a narrative function or contain an intertextual reference (see chapter 2.2.4), and decide whether they should be included in the AD;

- Decide how you will indicate that text on screen appears. Possible strategies include adding a word or an explanation before reading it ("A caption reads"), changing the intonation, using another voice (male/female), using earcons (sound indicators) or integrating the content in the AD (for instance, "In 1941, a man…");

The description of subtitles or AST is discussed in much more detail in chapter 3.3.

Finally, keep in mind that certain countries have laws and regulations concerning the use of credits and logos. This is particularly important when a certain text on screen, such as credits, is left undescribed or is paraphrased.

Examples